Amphibians

Amphibian Monitoring on Mt. Mansfield

After an initial amphibian survey and establishment of monitoring protocols, populations of amphibian species have been monitored almost annually on Mount Mansfield since 1993. This monitoring has established baseline information of abundance for the species caught in drift-fences from which trends in abundance over time can be discerned. The monitoring also records changes in number and type of obvious external abnormalities. Amphibians are targeted for this kind of study because their multiple habitat usage and permeable skin make them especially sensitive to changes in environmental conditions and land use patterns. This is the longest-running set of amphibian monitoring data in the state.

In addition to intensive amphibian monitoring on Mt. Mansfield, data on all of Vermont’s reptiles and amphibians are gathered for the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas. This includes inventory and basic natural history data on all reptiles and amphibians found within Vermont.

The Data

Currently, drift fences are located at two elevations on the west slope of Mt. Mansfield: two at 1200 feet and one at 2200 feet. Amphibians that encounter a fence must turn to one side and many eventually fall into a bucket. Lids are removed from the buckets in the late afternoon on rainy days, and the captured amphibians identified and counted the following morning.

Due to an anticipated break in the funding the drift fences were removed from Mt. Mansfield during the summer of 2015. Luckily, funding was restored, the fences were reinstalled in May of 2016 and data collection began in June of 2016.

Because the re-installation of fences occurred in the summer of 2016, no data were collected in April and May 2016. In order to be able to continue comparing year-to-year results we needed to have a full year of results, including a spring migration in April and May. We chose to include the data collected during April and May 2017, as it was the closest chronologically to the 2016 field season and encompasses one full year. This report contains all data collected in the 2017 season, and the next report will follow the 2018 field season.

2017 in Summary

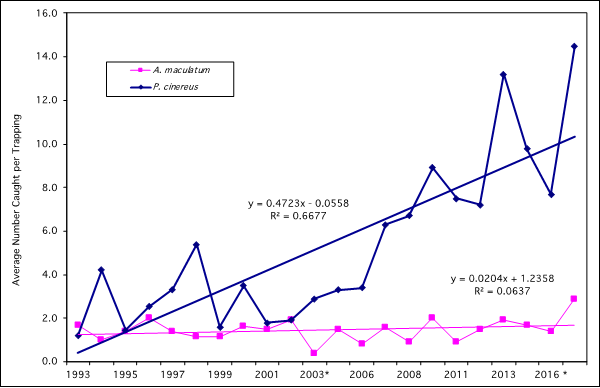

Overall, the total number of salamanders and frogs detected per trapping is higher than last year. Numbers were the highest ever detected for Spotted Salamander, Spring Salamander, Eastern Red-backed Salamander, and Wood Frog.

Spring Peeper captures continue to improve and this year resulted in the highest rate of catch (1.8 per trapping) since 1995. Although the long-term trend has not turned around yet, the increased number of adult Spring Peepers caught during the 2017 monitoring (mostly in early 2017) may signal the beginning of a recovery.

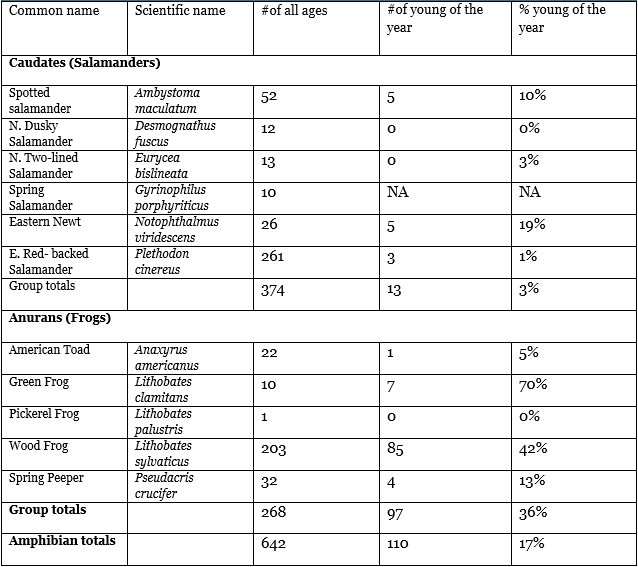

In 2017, the usual five caudate (salamander) species were caught as adults. In addition, we also caught adult Spring Salamanders (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus). Young of the following salamander species were also caught: Spotted Salamander, Eastern Newt, and Eastern Red-backed Salamander (Table 7).

In 2017, adults of all six of or our normally trapped anurans (frogs) were caught. Juvenile Wood Frogs were abundant (85). There were a few young Green Frogs (7) and Spring Peepers (4) but only one young American Toad and no young Pickerel Frogs or Gray Treefrogs (Table 7).

No abnormal anurans were collected in this most recent data set. Since 1998, only 14 abnormal anurans have been captured at this site.

Long Term Trends

A few species show clear long-term increases (Eastern red-backed salamander, Northern two-lined salamander, and American toad), while most species population indices remain constant (Figure 25). Long-term trends in amphibian populations vary year to year and in protected habitat, amphibians can generally hold their own. The major threat to populations is habitat loss and fragmentation due to development. Climate change is also problematic causing annual cycles to be disrupted. A late frost or spring drought can significantly impair amphibian reproductive success. The Mt. Mansfield site is relatively undisturbed by development making it more useful for detecting changes caused by climate or other abiotic factors.

Beginning with the 1995 report, we began documenting the number of young of the year (YOY). In 2017, young of the year made up 17% of those caught (Table 7). Over the course of the entire study (1995-2017) the average percentage of young of the year of total catch was 27.5%. Since the study’s inception the young of the year have varied from 11% (2014) to 74% (2002). Over the length of the record, Wood Frog YOY showed a high in 2003 of 59% when Spotted Salamander YOY were also high at 50%. In contrast, Wood Frogs showed their lowest percentage of YOY in 2012 (4%) while Spotted Salamanders were at a fairly high 40%. One possible difference is that Spotted Salamanders are more resistant than Wood Frogs to a variety of potentially threatening conditions such as predation, short-term draught, winter kill and late season freezes in their breeding ponds. The spring temperatures have varied a great deal in the past few years with some Wood Frogs moving at record early dates elsewhere in Vermont. This could result in fatal freezing temperatures after eggs were laid. Spotted Salamanders over-winter well below the frost line. In contrast, Wood Frogs freeze and thaw in the leaf litter and are very susceptible to winter kill if soil temperatures drop low enough. Another interesting correlation is that the increased annual variation of Spotted Salamanders began in 2002, the same year that Green Frog populations soared, Wood Frog populations peaked, and E. Red-backed Salamanders began their impressive increase. The different life histories of these species may provide some clues as to what is driving declines in Spring Peepers at the same time that we see long-term increases in other species such as Eastern Red-backed Salamanders.

Implications

The data collected about reptiles and amphibians from Mt. Mansfield, Lye Brook, and from the participants in the VT Reptile and Amphibian Atlas have been used to provide conservation information to private individuals, companies and organizations and governmental units. Biologists from Green Mountain and Finger Lakes National Forest asked for advice on reptile and amphibian management, private foresters consider herptiles in their management plans, citizens and the Vermont Department of Transportation assist in road crossings during spring migratory periods, and critical habitat for rare or threatened species has been purchased. All species benefit from these conservation measures. The continuing decline of several species of amphibians in Vermont should be cause for concern for all of us.

Adult Spring Peeper captures in 2017 surpassed those of 2016 showing potential recovery in light of long-term trends of decline.

Additional Resources

- Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas http://vtherpatlas.org/

FEMC Project Database Link

- Amphibian monitoring at the Lye Brook Wilderness and Mount Mansfield https://www.uvm.edu/femc/data/archive/project/amphibian-monitoring-lye-brook-wilderness-mt